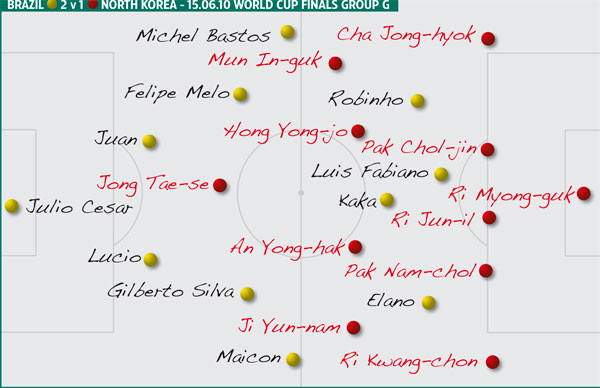

Unable to compete with Brazil on equal terms, North Korea opted for a damage limitation 4-5-1 line-up

A year ago it seemed that football might be entering a new age of attrition. Internazionale had won the Champions League playing reactive football, halting – with the help of an Icelandic volcano –Barcelona’s tiki-taka parade and revelling in the fact that they had only 16 per cent of possession in the second leg of their semi-final win.

Tiki-taka prevailed in the World Cup, but it was a glum form of it, as Spain, faced with massed defences, simply circulated possession, knowing a mistake would be made and a goal would come eventually. They were the best side at the World Cup by a distance, probably the most deserving World Cup winners – in the sense of being demonstrably better than the opposition – since West Germany in 1990, yet eight goals scored in seven games tells its own story. When Arsene Wenger spoke of “sterile domination”, he was talking about Barcelona, but the term is surely more applicable to Spain.

As it turned out, though, the season that followed the last World Cup wasn’t much different to the previous one, with the exception that this time, without any volcanoes to stop them, Barcelona passed their way to a second Champions League in three years. Watching club sides again, both in domestic action and in the early qualifying rounds of European competition, there was a tremendous sense of release; after the stodginess of the World Cup, here were teams playing with attacking fluency. When even the opening stages of a club competition are a breath of fresh air, the World Cup has a major problem.

There hasn’t been a good World Cup since 1998, and even that has gained in lustre by comparison with what has come since. In Japan/South Korea and Germany it was possible to blame the weather (although it was hot in France), but the South African winter should have been ideal for football. There was controversy over the balls and talk of player fatigue from their domestic seasons, but a significant part of the issue was tactical.

Over the past two decades, football has become increasingly systematised, a point made clearly in the UK’s Guardian newspaper each week by the “Secret Footballer”, an unnamed Premier League player who, from behind his anonymity, has cast off the code of omerta that so often seems to prevent footballers from speaking openly about their craft.

“The level of detail that goes into games still, to this day, amazes me,” he wrote. “Every player has his own script, what to do, when to do it, information on the player he’s up against…we memorise every single set-piece, where we have to stand, run and end up – and even for the other players so we know where everyone else will be at any given time.

“You know that pass when you say to yourself: ‘How did he spot that?’ Often he didn’t need to; he knew the player would be there because, the night before in the hotel, he read about the runs he would be making. It’s exactly the same pass after which you might say: ‘Who was that to?’ The receiving player either forgot to be there or was taken out of the game by a tactical manoeuvre by his opposite number. Football at this level is very chess-like, certainly to those inside the game.”

At club level, players have weeks to learn those moves as they train together day after day, and play perhaps 50 games a season. Over time, a mutual understanding develops, the “chess-like” moves becoming instinctive. At international level, though, in the limited time available, it’s impossible to achieve that coherence. Moves are less slick because players constantly have to look for team-mates rather than knowing intuitively where they’ll be – a difference of a fraction of a second that is compounded over the course of a long move, making it easier for defenders to get wise and cover.

So most managers start with the basics and pack men behind the ball. If defenders or holding midfielders go forward, they risk leaving spaces that, at club level, would be filled by team-mates. Most are far less adventurous for their countries, maybe fearing the consequences of a mistake, the effects of which are magnified by relatively few international fixtures played – and the result is the “broken teams” that characterised the last World Cup.

Even Holland – whose “Total Football” in the 1970s introduced the world to new levels of internal coherence and movement – effectively played with six defenders and two forwards, linked only by Dirk Kuyt’s industry and the creativity of Wesley Sneijder.

The problem is intensified by the number of mismatches at the World Cup, borne out by the confederation tournaments in which the standard is less varied. A 32-team event feels bloated but, more than that, the need to satisfy every confederation means they’re not even the best 32 in the world. The likes of North Korea, New Zealand and Algeria have little option but to defend or risk a hammering. Defensive football is, as the great Italian theorist Gianni Brera put it, “the right of the weak”, but then what are the weak doing at the World Cup in the first place?

For now, international football draws much larger audiences than even the best club football, but the gap is closing. Empty stands in South Africa and estimates that only two-thirds of the expected 450,000 overseas visitors materialised must also be troubling. What if this is evidence not of the global economic crisis but of a growing disillusionment with international football? What if frustration at the lack of quality and entertainment starts to outweigh the patriotic urge to watch games?

Bad football, no matter how packaged, cannot be a spectacle forever.

Those countries who missed out on hosting the World Cup in 2022 may feel they had a very lucky escape.

By Jonathan Wilson