Marcelo Bielsa might be known as “El Loco” but he is far from stupid, and his decision to turn down Internazionale in the summer was rooted in the most worldly of considerations.

And as Gian Piero Gasperini’s ill-fated five games in the San Siro hot seat demonstrated, the grandees of the game simply don’t have time for radicalism – particularly with Inter’s ageing, slow squad simply unsuited to the sort of hard-pressing game favoured by both Bielsa and Gasperini.

Instead of Italy, Bielsa went to Spain, where he joined Athletic Bilbao, a club almost as idiosyncratic as he is.

They had finished sixth and reached the Final of the Spanish Cup last season under Joaquin Caparros, whose legacy is tainted by suggestions that he was little more than a long-ball merchant. Successful he may have been, but there was little outcry when Josu Urrutia won the club presidential election in the summer and didn’t renew Caparros’ contract. It may, in fact, have been Caparros’ style of football that was one of the reasons Urrutia won the election.

In some ways, Caparros fitted with Athletic’s tradition. As an exhibition in the museum at San Mames stadium makes clear, Athletic is a very British club. It was founded by English shipyard workers and its style was instilled by Wolverhampton-born Fred Pentland, a stern, moustached figure who bade farewell to his bowler hat shortly before the end of each of his five Spanish Cup successes, knowing full well that his players would jump on it in triumph.

Pentland was regarded as a radical coach who favoured a short-passing game (although what was short in the 1920s would probably look pretty direct to modern eyes), but he still liked his centre-forwards big and robust, and his centre-backs more so. The likes of Fernando Llorente and Fernando Amorebieta are the modern incarnations of that tradition.

It’s a difficult line for coaches at Athletic to tread: they must be direct enough to reflect the traditions of the club but not so direct as to be accused of being long ball. In that regard, Bielsa may be the perfect compromise. He is far from a long-ball coach, but he does prefer “vertical football”. He is an idealist; not in an aesthetic sense, but from the point of view of having a clear conception of the sort of football he believes works, with his opinions honed from a library of tens of thousands of videos and careful statistical analysis, all charted in multi-coloured diagrams and spreadsheets.

Bielsa wants the ball to be won high up the pitch and so advocates intense pressing; speaking, as Arrigo Sacchi did, of there being an ideal 25 metres between centre-forward and centre-back. He recognises the importance of the rapid movement of the ball from front to back to catch opponents off balance, but he also sees the value in retaining possession, which is what differentiates him from, say, Egil Olsen, a coach who always prioritises position on the field over possession.

Inevitably, though, it took Bielsa time to settle in Bilbao. He made radical changes, offloading nine players, and training became far more conceptual, with moves worked through in detail without opponents. While Caparros’ sessions were focused on 11-a-side matches, Bielsa has played just one full practice game since taking over.

But there have been encouraging signs that Bielsa’s methods are paying off and that he has begun to adapt to his new surroundings.

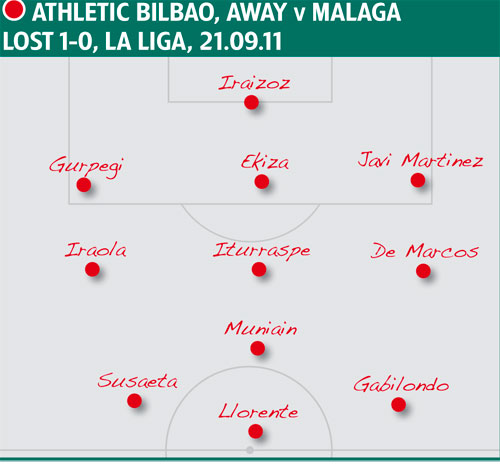

His early experiments with the 3-3-1-3 that he had used with Chile have been replaced by a back four, usually but not exclusively, in a 4-2-3-1 shape. He has limited his habit of playing a midfielder in defence and started to pick the left-back Jon Aurtenetxe. There is also a clear effort being made to utilise the wings, and the occasional long, diagonal ball is used to make the most of Llorente’s aerial ability. Llorente himself has been magnificent this season, leading the pressing with such energy and focus that at one point in the Europa League game against Paris Saint-Germain he closed down a free-kick before it had been taken.

There is evidence, too, of the pre-planned moves starting to work. Against PSG, Athletic responded to a packed defence by plying low, hard balls forward, with a player dummying and carrying on his run, looking to receive a lay-off. It was from precisely this route that the opening goal came. Javi Martinez hit forward a pass of perhaps 30 yards; Oscar De Marcos dummied, pivoted and kept sprinting; Llorente helped the ball on and De Marcos crossed to the far post where left-winger Igor Gabilondo hooked a volley into the top corner – a wonderful strike to end a wonderful move. Three passes had sliced open a defence that had six men behind the ball.

After five league games without a win at the start of the season, victory over Real Sociedad in San Sebastian, a draw in Valencia and a 3-0 dismantling of Atletico Madrid at San Mames suggested just what a force Athletic could be. They are also through to the knockout stage of the Europa League. And yet, at most clubs, Bielsa would have been under severe pressure after those first five games, while at Inter he would probably have been sacked.

That speaks of a wider flaw in modern football: the fact mavericks like Bielsa only get their chance at mid-ranking sides like Athletic. Perhaps that’s always been true to an extent – after all, Brian Clough lasted just 44 days at Leeds United, the only truly big club he ever managed – but the difference now is that talent is so concentrated at such a small handful of clubs it’s impossible for mid-ranking sides, even when managed by a genius, to challenge the best. Clough won a league title with Derby County and a league and two European Cups with Nottingham Forest, while Bielsa is left to battle for Europa League qualification.

Were he a generation or two older, Bielsa would have been challenging for the greatest prizes; as it is, his genius is doomed always to bubble a little below the surface.

By Jonathan Wilson