Tim Vickery‘s Notes from South America

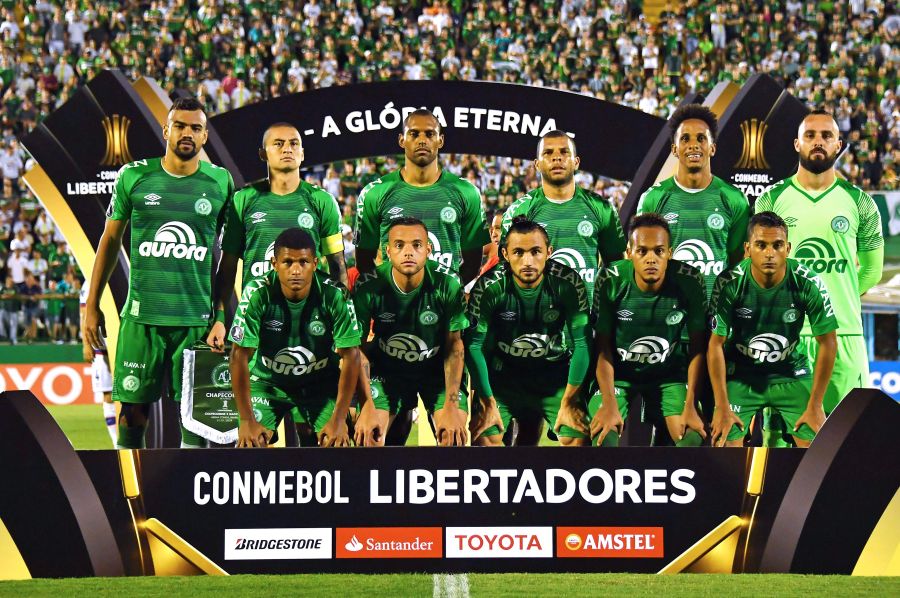

After that tragic air crash in late November 2016, the only aim of Chapecoense in last year’s Brazilian championship was to avoid relegation to the second division. To finish eighth was a magnificent achievement with an unexpected bonus – a place in the qualifying rounds of the Libertadores Cup, South America’s Champions League.

But the continental adventure could come to a swift end. In last Wednesday’s first leg they were deservedly beaten 1-0 at home by Nacional of Uruguay – who had got the better of them in last year’s debut campaign.

Chapecoense, though, still have two chances of making it through to the group phase.

One, of course, is on the pitch. It is by no means beyond the capabilities of the club to win in Montevideo. A 1-0 victory would take the tie to penalties. Any other margin would carry Chapecoense through and eliminate a Nacional team who, last Wednesday apart, have looked far from convincing this year.

The other route is through the sports justice system. In Chapecoense’s stadium last week, two fans of Nacional were clearly seen mocking the little Brazilian club in a grotesquely tasteless manner, making aeroplane gestures in a deplorable reference to the 2016 tragedy in Medellin.

It is an under-statement to declare this type of behaviour unacceptable. But to what extent are Nacional responsible for the actions of all of their supporters?

This question is at the centre of the case which will be now be debated. Chapecoense have called for Nacional to be kicked out of the competition. CONMEBOL has opened disciplinary proceedings – currently due to start from Thursday, a day after the second leg in Montevideo. Chapecoense would like the match to be postponed until the disciplinary case has been heard.

Nacional, it would seem, have no desire to protect their two delinquent fans. The club repudiated their actions and cancelled their membership. The Uruguayan club have not been responsible for any breach of security, and so eliminating them from the competition would be an extreme act. Then again, we are dealing with an extreme case of anti-sporting behaviour. It may well be that the most adequate way for the matter to be dealt with would be for Nacional to be forced to play the match behind closed doors – the type of punishment recently handed out to Flamengo of Brazil after some of their supporters went on the rampage before and after December’s final of the Sudamericana Cup.

The problem here, of course, is the lack of time available to implement such a measure – and, with a tight calendar, the difficulties of postponing the game to a later date. The winners are already scheduled to be in action next week, at home to the victors of the tie between Independiente del Valle of Ecuador and Banfield of Argentina.

But even if Nacional do hold on to their advantage on Wednesday, there would be some value in forcing them to play the following game in an empty stadium. Because the Chapecoense disaster did much to bring the continent together. An empty stadium in Montevideo might serve as a reminder of those days when a small town in southern Brazil was at the centre of a grief which, for a while at least, transcended nationality.