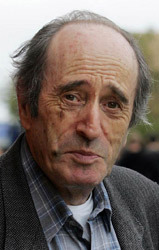

So Roy Keane has gone, in sullen silence and without him, a Sunderland team beaten in his last game in charge, at home, 4-1 by modest Bolton, have promptly gone into the cauldron of Old Trafford and held out until injury time, going down 1-0 at the very last gasp.

True, Sunderland played pretty well the whole game in a defensive crouch, but surely that tells you something about what has been going on at the grandiosely named Stadium of Light.

Roy Keane didn’t even turn up to say goodbye to the players, and he apparently resigned by fax, without a face-to-face farewell with his fellow Irishman, loyal admirer and Sunderland chairman, Niall Quinn. The thrashing by Bolton was merely the last of a string of dismal results, yet Sunderland still owed it to Keane that he got them out of the so-called Championship – it will always be the second division to me – and indeed kept them there.

Whether he would have been able to do so this season who can say, but his team appeared to be in free fall, his extremely costly transfer policy a failure, his chopping and changing doing nothing to improve results. You couldn’t help feeling, after the defiant display at Old Trafford, that it might have been a case, as they sang in The Wizard of Oz, of Ding Dong, The Witch Is Dead.

Keane did better at Sunderland than I thought he would, but right from the beginning I expressed the view that his players would not be able to contend with his fierce perfectionism. As a player, and an excellent if ruthless one, he gave himself no quarter and one feels that as time went by at Sunderland, he had less and less patience with his players.

You wonder to what extent he was reacting to the image of a father, far less focused and disciplined, by all accounts than he. There have been chilling episodes in his playing career, notably those involving the Norwegian Alf Inge Haaland. Keane wouldn’t forgive him for an injury suffered when playing for Manchester United at Leeds, which by all accounts was self-inflicted. That is to say, it was his own foul on Haaland which caused him such pain and anguish, keeping him out of the game for months and prompting him to await his revenge. It duly came when Haaland was playing against him for Manchester City in a local derby.

With supreme satisfaction Keane, in his ghosted autobiography, recounts how he savagely and deliberately fouled Haaland, and furiously berated him into the bargain. You might have thought that the ghost of his autobiography, Eamonn Dunphy, once himself at times an Irish international, later to become a successful author and television pundit, might have tactfully toned down Keane’s vitriolic words but he didn’t. Surprisingly, he was one of Keane’s most dismissive critics hen Roy walked out on Sunderland.

In a highly revealing confession, Keane has given us some insight into his managerial philosophy. At an early stage with Sunderland, he has recounted, he found himself actually sitting down and eating with his players, realised what a serious mistake he had made and never did it again.

Well, there is no doubt that a manager can indeed get too friendly with his players, thereby losing his command over them, but Keane surely seemed to take detachment too far; almost one felt to the point of hostility. By the time he left, the word was that the players were in fear of him, and were only too glad to see him go. Whether the legacy he has left behind him will be sufficient to keep them in the Premier League, time will tell.