Diego Maradona: a tribute

Back in 1975, staring at me out of the pages of long-gone Argentinian sports magazine El Grafico, was a stark colour picture of delight of a tousled-haired 15-year-old. He was captioned as Diego Armando Maradona. He was a kid from the wrong side of the tracks who would rule the world.

Maradona was making his debut for Argentinos Juniors in troubled times. Argentina was tumbling out of political turmoil into the long dark years of the military junta. For the Generals, distractions were essential. Like hosting the World Cup in 1978.

Maradona might even have played in that World Cup after making his debut against Hungary at 16 years 120 days. Instead, he was one of three players dropped on the eve of the finals when coach Cesar Luis Menotti trimmed the squad. Maradona stormed out of the camp and wept for three days.

The next year, Maradona captained an ultimately triumphant Argentina at the World Youth Cup in Japan. That proved to be one of 12 trophies he’d win during his career and which would glitter out of the multiplicity of pictures unearthed in the world’s photo archives on his death at the age of 60.

Argentina’s media had been on tenterhooks for years awaiting the day which would convulse a nation. Every time the rumour mill claimed that “El Pibe de Oro” (Golden Boy) had been taken ill, so the editors cleared the decks for the worst. As daily paper Clarin reported with that long-awaited, long-feared finality on November 25, 2020: “This had to happen one day.”

The first day was October 30, 1960, in the intimidating Villa Fiorito shanty in the province of Buenos Aires. There was no easy way out. At least football was one. At nine Diego began playing for a kids team named Estrella Roja (Red Star). Later he and his friends founded a team called Los Cebollitas (The Little Onions). They were turned en bloc by Argentinos Juniors into one of the club’s youth sides.

On October 20, 1976, Maradona made his debut as a 15-year-old substitute against Talleres of Cordoba. A week later came his first start against Newell’s Old Boys. The next 44 years would be fraught with contradictions and conflict between Maradona the footballer on one hand, and Maradona the controversialist on the other.

Initially the footballer ruled. He was the classic Argentinian No.10, denoting a team’s creative fantasist. Boca Juniors, team of his dreams, bought him for £1 million in 1981, leaned on his gifts to win the championship, then sold him to Barcelona for £3m in 1982 – a then world-record transfer.

On the way Maradona succumbed to the pressures of the World Cup, in Spain in 1982. He was a marked man. The official film records Italy’s Claudio Gentile tracking him relentlessly, step by step, in a 2-1 defeat. Ironically, when Maradona’s patience snapped, it was Brazil’s Batista next time out that felt the full force of a boot in his groin. Red card for Maradona. Welcome to Spain.

Maradona’s first season there was interrupted by hepatitis; his second by a notorious wrecking tackle from “The Butcher of Bilbao”, Andoni Goikoetxea. The two players renewed hostilities in the 1984 Copa del Rey final. Maradona was at the centre of a mass brawl in front of King Juan Carlos. He had to go.

His destination was Napoli, for yet another world record – £5m this time. Within weeks, Napoli sold a staggering 70,000 season tickets. The shady source of the transfer cash guarantee was an open secret. Maradona inspired the club to its first two Serie A titles, two second places, a Coppa Italia and Supercoppa as well as the UEFA Cup.

Increasingly, however, Maradona became entangled in his own fame, the claustrophobic adulation, the money, the girls, the drugs…and the Camorra.

The maelstrom of entrapment was captured frighteningly in Asif Kapadia’s film, Diego Maradona. Personal trainer Fernando Signorini expressed the dichotomy of his self-destructive genius perfectly, saying: “For Diego, I would go to the end of the world, but for ‘Maradona’ I wouldn’t take a step.”

At this point in the 1980s Maradona the footballer could do no wrong. His skill, perception, awareness, range of passing, technique and match-reading were sublime. His left foot magnetised the ball and his skills mesmerised both opponents and fans. Especially Napoli fans who worshipped him with shrines.

Simultaneously Maradona turned Argentina into world champions once more in 1986 in Mexico, usurping 1978 skipper Daniel Passarella as captain shortly before the World Cup. This writer was sitting in the Estadio Azteca for the quarter-final against England: we saw what the referee did not, the “Hand of God”. We also all saw the lightning-touch acceleration with which Maradona ghosted through England’s defence for his second goal.

He darted in from the right on that occasion then, barely remembered now, scored a mirror-image goal, cutting in from the left this time, in the semi-finals against Belgium.

Victory over the old colonialist England, coupled with the cheek of its achievement, was a gesture of national retaliation after the Falklands War. The “Hand of God” expressed a defiance of society’s establishment with all its restrictive rules and regulations. This was why so many millions loved him: Maradona: mocked officialdom in a way they dared not. The more outspoken he became, so the greater the adulation but the more inevitable the revenge of an unforgiving ruling class.

The 1990 World Cup in Italy was the beginning of the end. Maradona played inspirationally again, despite badly damaged ankles. He even missed a penalty in the quarter-final shoot-out against Yugoslavia but Argentina still reached the semis. Drama piled upon drama: the draw matched Argentina and Maradona on his adopted home ground in Naples against Italy.

Maradona appealed to depressed southern Italy in general, and Napoli fans in particular, to support him as a gesture against the Italy of wealth and privilege. But when Argentina won on penalties, Italy fell out of love with him. In the final Argentina had two men sent off and lost 1-0 to West Germany on a contentious late spot-kick. Maradona, in tears at the final whistle, furiously blamed a conspiracy between FIFA’s Brazilian president Joao Havelange and Italy’s governing elite. Suddenly Maradona was no fun any more. The balance of power tipped against him.

The cocaine parties after Napoli’s weekend matches had been an open secret. Dope testers turned up regularly but only later in the week when illicit substances had been sweated away. That was the deal. Until March 17, 1991. Then a test from a post-match swoop after a 1-0 victory over Bari came up positive. Revenge served cold. He was banned for 15 months.

Maradona sought to revive his career in Spain with Sevilla and again with Newell’s Old Boys, before leading Argentina to the 1994 World Cup. There, in a press conference in Dallas, FIFA decreed this comeback over with a dope test for ephedrine and a new 15-month ban. He had played his 91st and final game for Argentina, scoring the last of his 34 goals.

A further comeback with Boca ended in another dope test, which forced permanent retirement. But abandoning the game that had been his life was out of the question. A string of short-lived coaching appointments followed in UAE, Mexico and Argentina (latterly with Gimnasia de La Plata). He even led Argentina to the quarter-finals of the 2010 World Cup in South Africa.

Along the way Maradona was treated for weight problems, drug addictions, a heart attack and a concoction of health issues. Yet he remained a magnet for fans and media everywhere.

He was still working with Gimnasia when he was diagnosed with a subdural hematoma in November and underwent emergency brain surgery. He seemed to have come through the operation and was released from the clinic when he suffered a fatal heart attack at his home in Tigre. Argentina declared three days of national mourning. Before the funeral his coffin lay in state at the Casa Rosada presidential palace.

So many stories: the financial fall-outs with his agents; the paternity suit brought by Cristiana Sinagra; friendship with Fidel Castro; firing an air gun at reporters outside his home; and the derisive barb he offered me five years ago about old FIFA president Sepp Blatter “who was chasing champagne while I was winning World Cups.”

Yet also the solo goal which brought admiring Real Madrid fans to their feet in his first season at Barca; a cameo at Tottenham in tandem with Glenn Hoddle at Ossie Ardiles’ testimonial; the reverse-passing magic with Careca at Napoli; and fans of so many teams who succumbed to his magic.

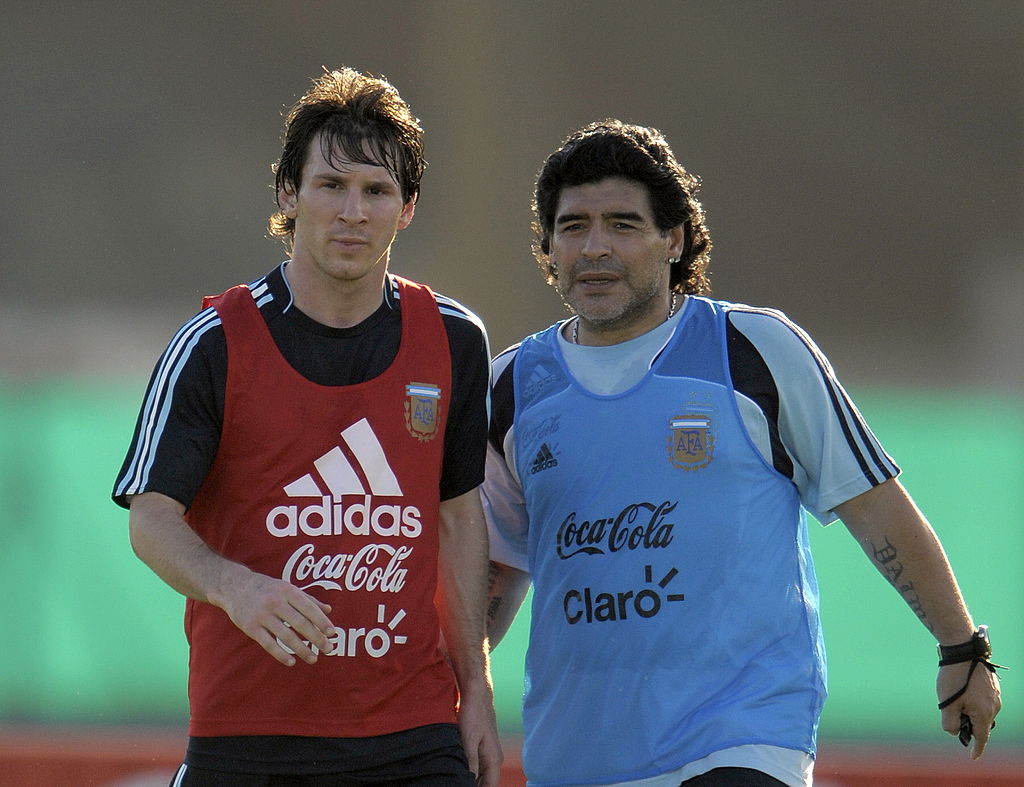

Maradona counts among the three greatest footballers I have had the privilege to watch in action, along with Pele and Alfredo Di Stefano. As for that third Argentinian, Leo Messi? A wonderful player but not on the same sporting stratosphere. With Maradona there was always a unique volcanic tang of barely repressed danger.

In the musical Evita, Tim Rice created words for Eva Peron that might equally serve as an epitaph for Maradona too:

“The choice was mine, and mine completely. I could have any prize that I desired. I could burn with the splendour of the brightest fire. Or else, or else I could choose time.”

Football will always honour the brightest fire that was Diego Armando Maradona.

Article by Keir Radnedge

This article first appeared in the January Edition of World Soccer. You can purchase old issues of the magazine by clicking here.